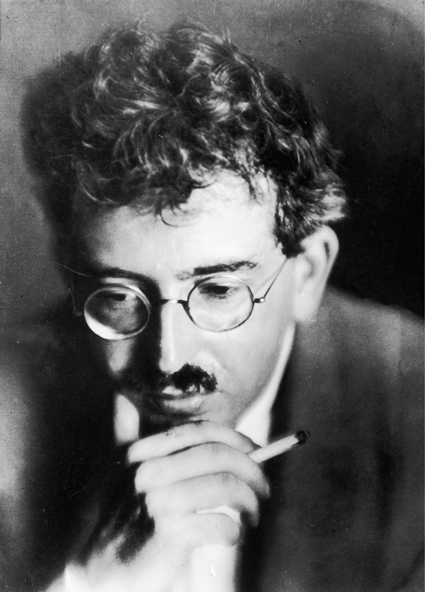

In ‘On the Concept of History’ (1940), the philosopher Walter Benjamin offered two conceptions of time: ‘homogenous and empty time’ and ‘Messianic time’. ‘Homogenous and empty time’ is the type of time recorded on clocks and calendars: an even, linear procession of days, months and years continuing endlessly into the future, where every moment counts the same as all the others. The biblical notion of ‘Messianic time’, in contrast, is uneven: it has moments of special, transcendental importance, of divine intrusion into the world – the Creation, the Fall, the Flood. In ‘Messianic time’ it is possible to move backwards, in a sense. The crucifixion of Jesus, for example, reaches back to the sacrifice of Isaac and ‘completes’ that event, revealing its true significance. Crucially, ‘Messianic time’, unlike ‘homogenous and empty time’, has an end point: the End of Days that is signalled, for Jews, by the gathering in of the diaspora and the coming of the Messiah.

The illusion of ‘Messianic Time’

In Gravity’s Rainbow (1973), Thomas Pynchon plays with the notion of ‘Messianic time’. At times, he dismisses it, noting that the End of Days never, in fact, arrives. As he writes, the ‘prevalent notion’ that ‘someday, somehow, before the end, [there will be] a gathering back to home. A messenger from the Kingdom, arriving at the last moment’ is misguided: ‘I tell you there is no such message, no such home — only the millions of last moments . . . nothing more. Our history is an aggregate of last moments’.

On this view, ‘Messianic time’ is simply a comforting illusion conceived to avoid the disturbing conclusion that time really is ‘empty and homogenous’ and will go on and on forever and ever, with or without us. There is no Messiah coming. This fact is felt bleakly by the Jews of the novel, consigned to the concentration camps that are depicted so vividly in the Part Three. In this section, we see the camps as a space consisting only to the dying and the dead, where no-one has been delivered by any saviour.

The rocket as the anti-Messiah

Pynchon also observes, however, that with the development of new destructive technologies, such the V2 missile (in some respects a precursor of atomic weapons), there is a real possibility that human history might come to an end, not with the coming of the Messiah, but with an equally sudden fall of a bomb. As Benjamin observed, if one believes in ‘Messianic time’, then the future is unknowable, since God could intervene at any moment, meaning that all one can know is that time is inescapably running out – for the Jews ‘every second was the narrow gate, through which the Messiah could enter’. Pynchon offers an alternative theory: it is not the Messiah that might come at any moment, instituting peace and justice, but the rocket, bringing death and destruction. Book One sets up this theme, where it is established that the V2 rocket, because it travels faster than sound, arrives, like the Messiah, without any warning signs of its approach: ‘Imagine a missile one hears approaching only after it explodes. The reversal! A piece of time neatly snipped out.’

In this sense, then, we really do live in a world governed by ‘Messianic time’, since it could all end at any moment, only in a darker manner than that suggested by Scripture. Yet the biblical sense of finality is sinister in its own way, in that the Day of Judgement is a moment when only the righteous will be saved, the rest being cast into hell. Again, Pynchon meditates on this idea in Gravity’s Rainbow, likening the fall of the rocket to a final, damning divine verdict on humanity. At the opening of the novel, which describes a city ruined by the blast of a bomb, the narrator states ‘You didn’t really believe you’d be saved. Come, we all know who we are by now. No one was ever going to take the trouble to save you, old fellow’. The rocket, in a sense, is the final apocalyptic judgment on mankind, a real doomsday weapon that makes concrete the visions of the end of the world imagined by the ancient Jews and Christians.

Links in time

‘Messianic time’ posits links between key episodes in the history of the world – the building of Noah’s Ark and the construction of the Church, for example – that reveal God’s providence, a redemptive thread running through time. Pynchon also suggests a series of links between apparently unrelated events in human history in Gravity’s Rainbow. This is done most clearly in a single episode in Book One, which touches on the colonization of Mauritius by Europeans in the seventeenth century, German imperialism in Southwest Africa, and the Nazi occupation of Europe. What links these events is not a story of redemption, but of genocidal violence: the hunting of the dodoes to extinction in Mauritius; the German massacre of the Hereros in Southwest Africa in 1904-8; the holocaust of European Jews in 1941-5.

History, Pynchon suggests, reveals not the guiding hand of a benevolent God, but the manipulations of an evil, murderous deity, such as Blicero, the ancient German Lord of Death, who is summoned at a London seance in Book One and is incarnated throughout the novel by Captain Weissman, the German military officer who served in Southwest Africa and who is in charge of the V2 rocket programme. Through Blicero we see a horrifying inversion of ‘Messianic time’ revealing a providential destiny of death rather than salvation.

The hope of redemption

Despite his dismissal and inversion of ‘Messianic time’, Pynchon nonetheless holds out the possibility that some type of redemption may be possible. He does this through his portrayal of the Zone Hereros. The Zone Hereros in many respects mirror the Jews, the originators of the concept of ‘Messianic time’: both are exiled peoples; both suffer under oppressive foreign domination; both are subject to genocidal violence. The Hereros, like the Jews, hope to attain their redemption, wish for the reunification of their people, the reclamation of their land, and for a time of peace and justice. In Gravity’s Rainbow they seek these ends in a fragmented post-war Germany through the construction of the 00001 rocket, the mirror-image of the 00000 rocket designed by Blicero/Weissman for the destruction of the world.

The construction of the 00001 rocket is explicitly likened to the coming of the Messiah: ‘the assembly of the 00001 is occurring also in a geographical way, a Diaspora running backwards, seeds of exile flying inward in a modest preview of gravitational collapse, of the Messiah gathering in the fallen sparks’. The Hereros, along the same lines, are likened to Jewish mystics, the ‘Kabbalists’, whose ‘holy Text’ or ‘Torah’ is ‘the Rocket’, the study of which will enable them to reckon with the End of Days.

At the end of the novel it is observed that ‘Manicheans’ see ‘two Rockets, good and evil, who speak together in the sacred idio-lalia of the Primal Twins (some say their names are Enzian and Blicero) of a good Rocket to take us to the stars, an evil Rocket for the World’s suicide, the two perpetually in struggle.’ Here Pynchon makes explicit the contrast of the Herero leader Enzian, who seeks the world’s salvation, a destiny in the heavens, and Blicero, who wishes only for the world’s suicide. In this sense, Pynchon offers hope that there may indeed be peace and redemption and these forces might still prevail over death and destruction. If the 00001 rocket triumphs, ‘Messianic time’ may yet end with the reign of justice.

Awesome write-up, thank you!

LikeLike